The female body as a battlefield

She is part of the feminist avant-garde of the 1970s, her works range from staged photography to body art and hang in collections such as the MoMA in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. In Germany, however, Annegret Soltau was repeatedly censored until the 2010s because of her often disturbing visual language. That has now changed fundamentally: in a retrospective well worth seeing, Frankfurt's Städel Museum presented Soltau's artistic fragmentations this summer. The artist also has two appearances at ART COLOGNE – both at the stand of Frankfurt's Anita Beckers Gallery and at the stand of gallery owner Richard Saltoun (London/New York/Rome).

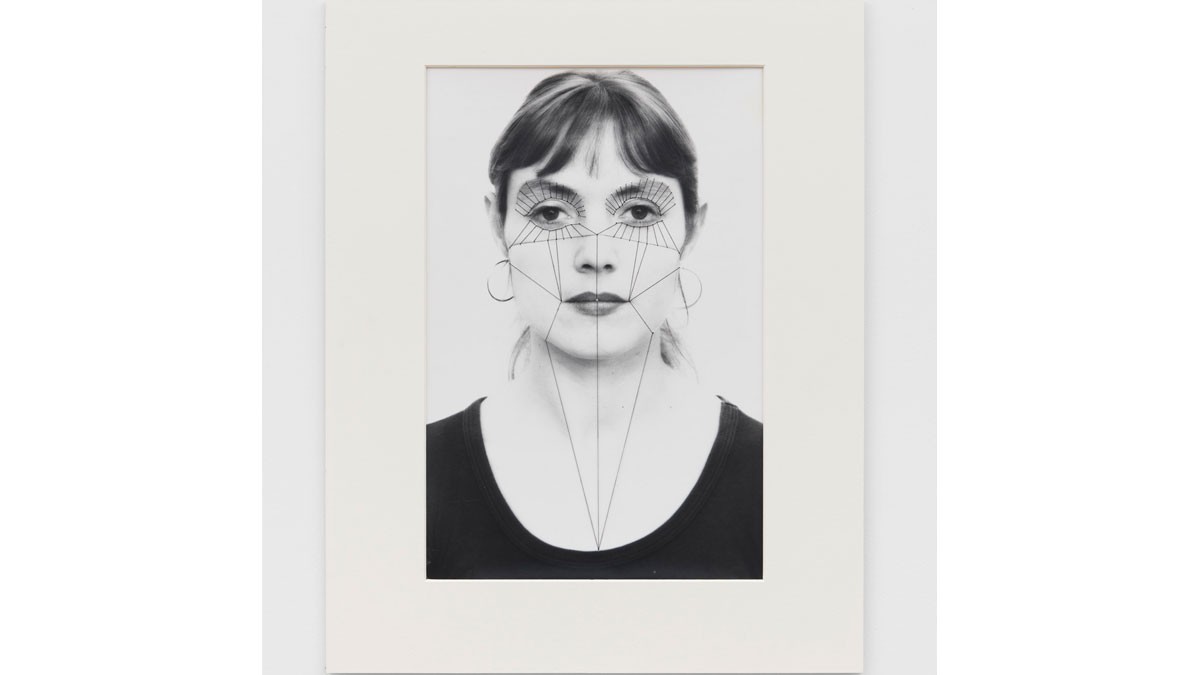

Annegret Soltau became known above all for her ‘photo stitchings’ – expressive collages with which she explored role models, social norms and representations of her own body. Destruction and rearrangement form the basis of her work. Soltau tears up photos and sews the fragments together with black thread. What initially appears chaotic turns out to be a powerful act of self-appropriation and a subversive reinterpretation of sewing, which has historically had female connotations.

Annegret Soltau „Permanente Demonstration am 19.01.1976“, 1976/2008, Set of 6 black and white photo etchings, Edition 1 of 5 (plus 2 AP. Photo: Richard Saltoun Gallery

Life as a constant violation

From the outset, she never strayed into the private sphere or voyeurism, but instead visualised injuries or contradictions. ‘I originally come from a background in painting and graphic art, and in my early works I also worked a lot with drawing and etching,’ she says. "I often depicted women who were “constrained” in some way. I enveloped the female figures in hair and let it flow over their faces and bodies like formations. This can be understood as both protection and restriction."

Soltau was born in Lüneburg, Lower Saxony, in 1946. She grew up on a farm with her grandmother. Her father was killed in the Second World War and her mother never accepted her. Before she began her studies, she worked for a trauma surgeon treating port accidents, as she received no financial support from home. At the Hamburg Art Academy, she studied under the Austrian painter Rudolf Hausner and the British artist David Hockney. She was part of the 1968 protest movement and painted a portrait of the future left-wing terrorist Ulrike Meinhof. In the early 1970s, she joined the new women's movement and began performing. In 1974, she moved with her former fellow student and husband Baldur Greiner to his hometown of Darmstadt. ‘New techniques were invented back then,’ she recalls, ‘performances were staged and things that were otherwise hidden were shown, especially the female body.’

Annegret Soltau „GRIMA – Selbst mit Katze (der Schrei)“, 1986, C-print Photo: Richard Saltoun Gallery

Vagina with needle pricks

That is why her collages often rely on provocation. In her series ‘Generative’, for example, she showed stitched-together body parts of her mother, her grandmother and herself. ‘Rape happens, episiotomies are performed during childbirth, and female genital mutilation still occurs in many countries,’ says Soltau. ‘The female body is a battlefield, and I want to show myself as I am, with the injuries that have occurred.’ For example, in distorted photographic works in which she photographed her vagina, which was ‘patched together’ with rough needle stitches after the birth of her child.

This extreme openness was not always well received. Her works were repeatedly subjected to public censorship. Motifs of pregnancy or birth, the search for one's own identity or self-optimisation still confront viewers today, not least with the respective zeitgeist. ‘When it comes to women's bodies, one gets the impression that they always have to be surgically altered in order to be allowed to be presented in public,’ she says. ‘I think that's wrong. The body positivity movement is currently being pushed back again. Ageing is also considered unattractive in our society; the wisdom of age is no longer seen or appreciated.’ Similar to how long it took for her own work to be ‘rediscovered’ by major museums and galleries – a belated, long-overdue recognition of an independent and extremely courageous oeuvre.

Author: Alexandra Wach